NOT FINAL : WRITING IN PROCESS

One of the most frequently asked questions I get, and one of my most popular topics in presentations, is explaining the difference between Offset Printing and Digital Printing, and most importantly, what the implications and relevance is for publishers, authors, and non-printing people. (*referred to as publishers henceforth for simplicity)

I’m going to explain this in layman’s terms and generalities for publishers, emphasizing the important distinctions and how they are relevant to a publisher. It will be vastly simplified (VS), there are obviously exceptions to a lot of this, and I’ll use some generic numbers to highlight an issue, not as a deeply precise accounting exercise. So hopefully my industry experts cut me some slack.

I like to throw a curve ball at people right off the bat:

Print on Demand is NOT a type of printing.

Digital Printing is NOT the same as Print on Demand.

Print on Demand is a BUSINESS MODEL that most often *uses* digital printing. Print on Demand simply means that the publisher doesn’t print books until an order is placed, and usually paid for. They are not printing large quantities of stock for inventory and fulfill orders in advance. In some cases, absolutely no physical inventory exists. Since most orders from consumers and resellers are small, these “on demand” orders are almost always fulfilled by using digital printing.

However, if one received an order for several thousand books, for example a privately branded edition of a business book, sponsored by a third party, that order would be printed “on demand,” but we’d use offset printing to manufacture the books. (We’ve actually had a client place multiple orders like this for his clients who wanted a customized version of his book). If your book becomes a smash hit, you might get a very large order from a discount warehouse club, and run a special “print on demand” print run just to fulfill that order (which is hopefully non-returnable discount in place).

Similary, all digital printing is not print on demand. The are many printers who use digital printing equipment who have designed their business (and their pricing) to fulfill short-run orders of 20-500+ books. Digital shor-run printing companies might be more flexible with more options, while a true PoD business operates on a limited product offering, round-peg-round-hole. They are competing in a different segments of the market.

The significance to you: The important thing for a publisher to understand is, the costs, overhead, and pricing from a printer set up to produce one book at a time, to fulfill an order, such as Lightning Source or Amazon’s KDP division, can be very different from a printer whose business model, workflow, and pricing is designed to process repeated orders of 100 or 200 books and ship to the publisher. You wouldn’t want to use a one-at-at-time printer if you needed 500 books, and you wouldn’t want to use a digital short run printer to process runs of 20 books (if they would even run the job).

Offset Printing vs Digital printing

Offset Printing

Offset printing is the traditional wet-ink-on-paper printing you’ve seen in movies, frequently showing newspapers being printed at blinding speed, and Gene Hackman running in yelling “stop the presses!!” Usually large machines that cost millions of dollars, with paper being fed thru from giant rolls or large pre-cut sheets. (VS) Presses might have 1-8+ different sections depending on if they are one-color, two-color, four-color, or more. If you are printing a full-color book, the press is using four sections with C, M, Y, K inks: Cyan, Yellow, Magenta, and Black. And it can get vastly more complicated, advanced, and expensive from there with special inks, coatings, finishes, etc etc.

This means your full-color book cover will be printed on one press on cover or jacket paper, while your black-and-white interior will be printed on a different press with text paper. Each press designed for a specific task, the right tool for the job. Cover and interiors will be married together during the bindery process.

There are similar variables concerning roll-fed presses (giant rolls of paper, very fast, lower costs), sheet-fed presses, (usually* higher quality and better papers) and varying sizes for each. Larger rolls or sheet sizes means more pages in one pass (larger signatures), meaning lower costs of manufacturing.

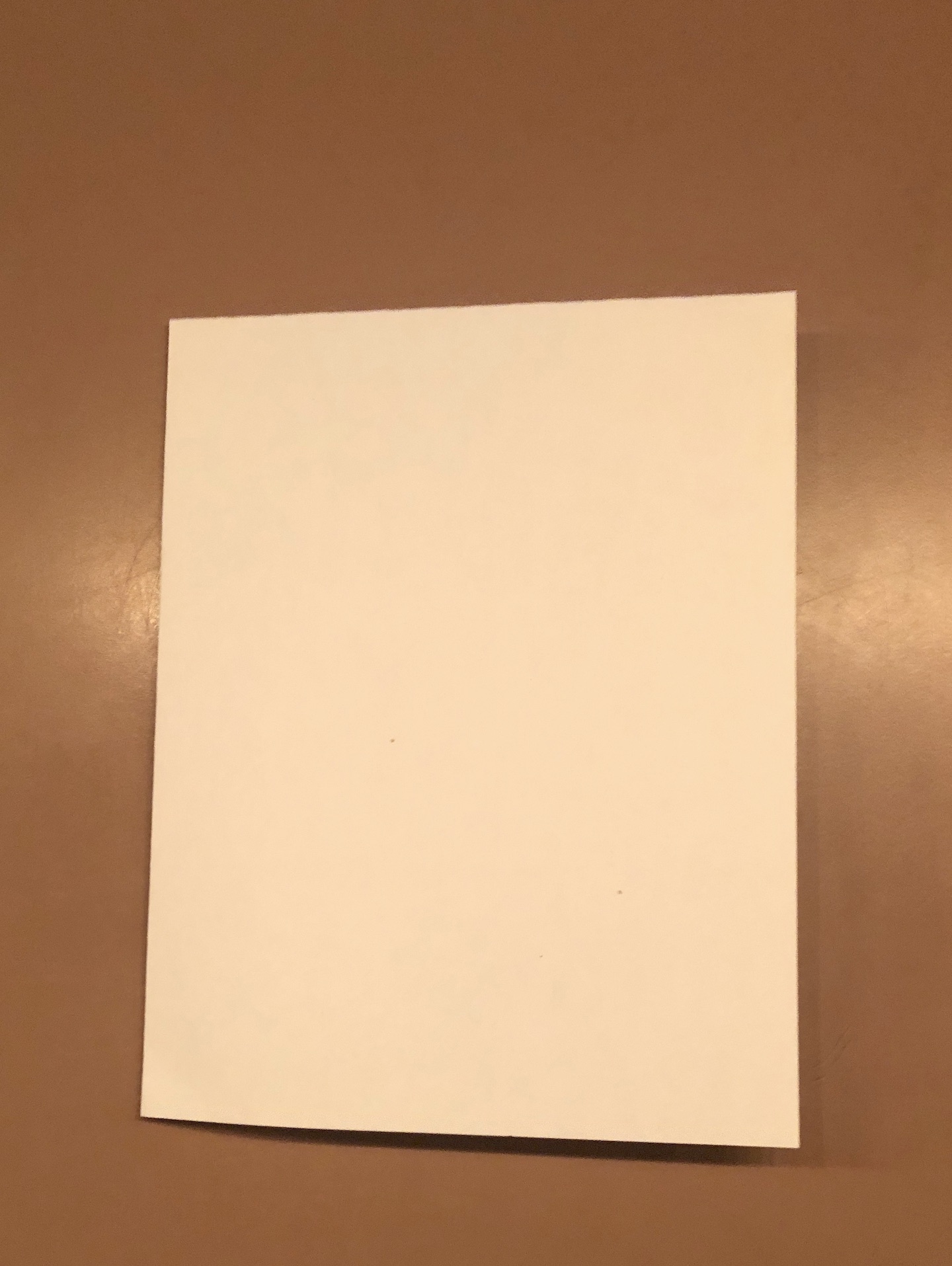

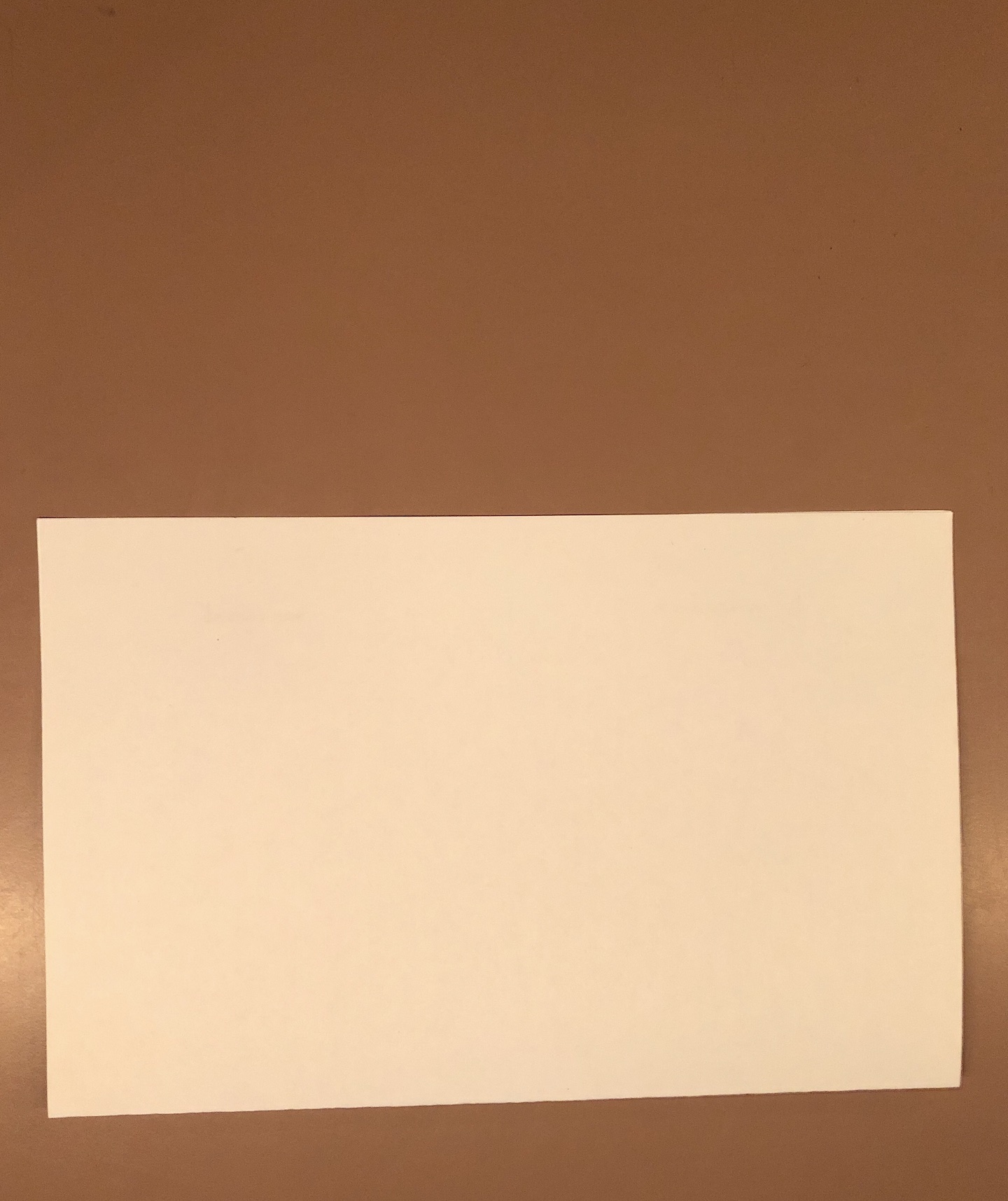

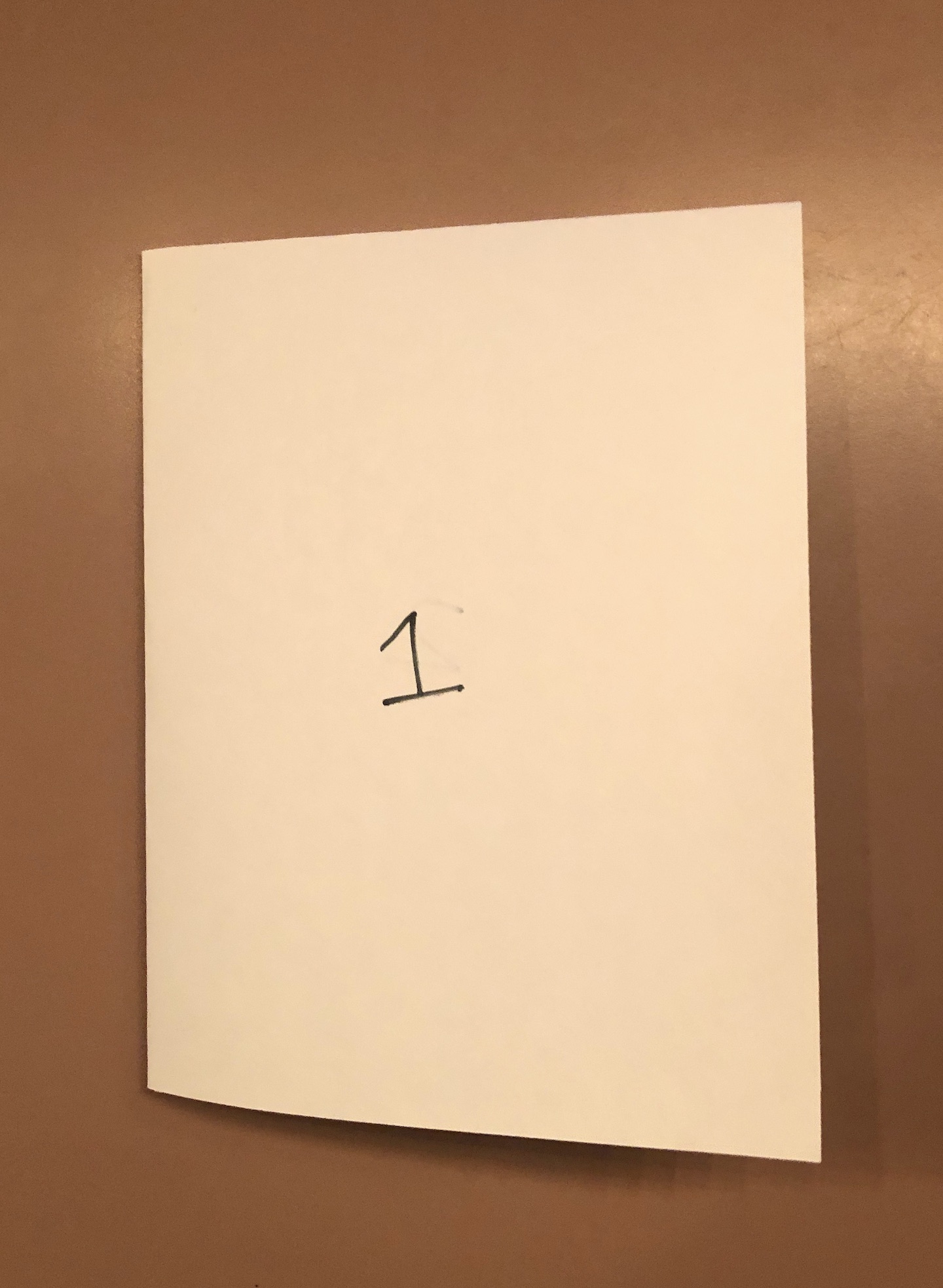

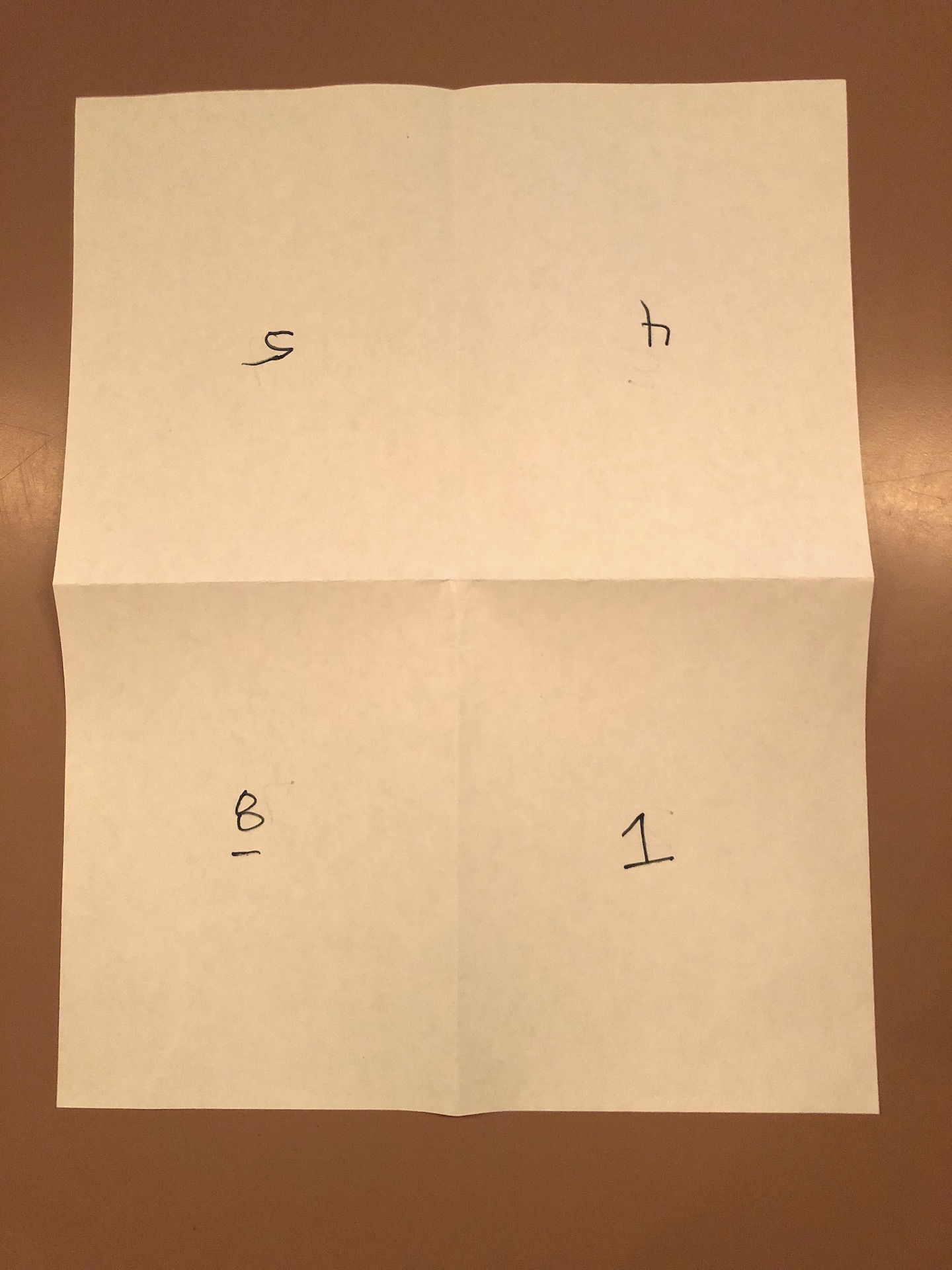

It’s important to understand that in offset printing, a book is printed in a series of “signatures,” a small batch of pages of your book. Take a piece of letterhead and fold in half lengthwise, and then horizontally. When you unfold it, you’ll see 4 small squares on each side. You have just created a miniature 8-page signature. Most printing presses are running 16-page signatures, and the machinery handles folding the paper into small “booklets” which will get stacked together (1-16, 17-32, etc), and eventually trimmed.

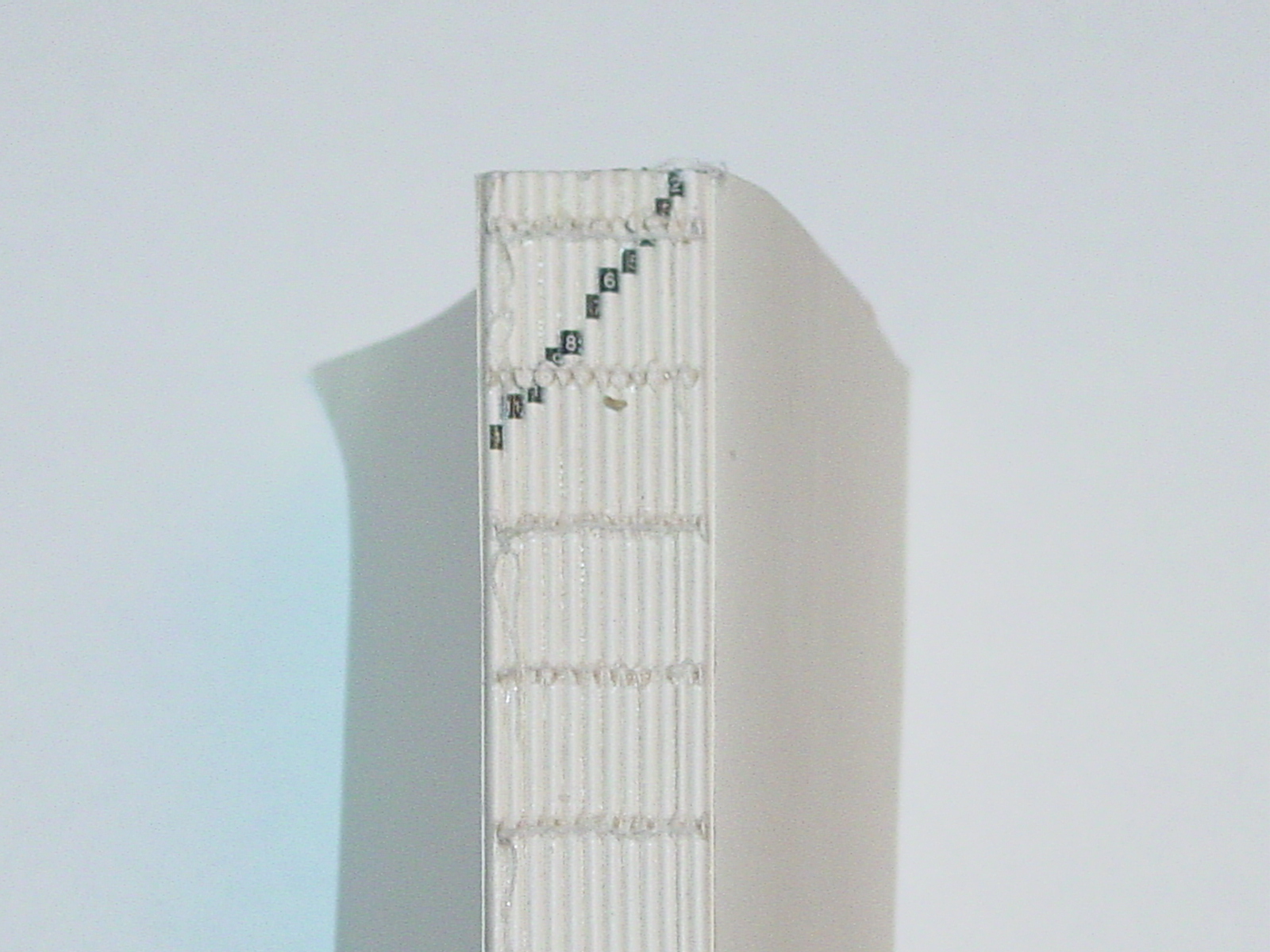

Look at the top edge spine of a book and you can usually see these signature folds.

The important thing to understand is that if you are printing 5,000 books, they are going to print 5000+ copies of pages 1-16, then 5000+ copies of pages 17-32, etc. None of the books are done until *all* of the signatures are printed in the same quantity. Stack all these on pallets, and eventually marry everything together using expensive and complicated machinery. So if you have a 160-page book, it will be produced using 10 press runs (16 pages x 10 runs = 160)

16 pages is the norm, and you’re almost always working in multiples of 8. It’s also dependent on the size of the book page itself (8 pages that are 8×10 are much larger than 8 pages of 6×9 etc–math!) Printers may use 8s (half sig), 32s etc, or even 24s depending on the size of the printing press.

The significance to you: If a printer has a larger press, taking larger rolls or sheets, they’ll produce 32 pages (or 24 pages) in one signature. 160 pages now means 5 press runs of 32 pages. Less set-up, plates, processing, changeover, downtime, etc etc. means lower costs.

Larger printers will have press lines dedicated to running only one trim size in giant signatures–very efficient and cost effective. The folding, gathering, trimming etc etc is all much more efficient if the manufacturing line is always producing 6×9 books.

The significance to you: you want a printer who regularly produces books similar to your book, because they have the equipment and workflow designed to efficiently produce that kind and size of book. You don’t want a Ferrari to take the kids to school, and you don’t take a minivan to the racetrack. And you certainly don’t want to PAY for a Ferrari when you’re just running for a coffee.

Digital Printing

Digital printing usually uses one of two methods: ink jet printing or toner-based printing. Again, vast over-simplification warning) Similar variables at play here as offset printing, with sheet and roll sizes, press sizes, etc. I can already hear my friends at digital printing companies and equipment manufactures screaming at me, but for your purposes as a publisher, think of these presses as extremely complicated and high quality (hopefully) laser printers and copiers. What you have in your office, but on tremendous steroids.

Digital printing, especially press lines designed for one-at-a-time printing, are frequently all-in-one, marrying the interior printing and cover printing into one workflow, binding, trimming, and BANG, a finished book comes out the end. Truly amazing technology. Load the file, push a button, make a book.

This technology has been improving in leaps and bounds for years, and will continue to do so. But it’s still different than longer run offset printing and can be subject to the variations that effect ink jet and toner based printing elsewhere. Colors may wander, image quality may vary, trimming accuracy and consistency can be an issue, and the quality and longevity of the binding may not hold up. Some of this can be caught and alleviated by a good quality control process, but some workflows aren’t optimized for that.

A short-run digital printing company, running jobs of 100-500 copies, can differentiate themselves as higher quality with better quality control, essentially catching and removing lower quality books. A one-book-at-a-time print-it-and-ship-it-immediately printer has a different value proposition.

Digital printing can be very high quality from very high quality equipment, but you as the publisher have to decide if it’s high quality enough for your project and your budget. For one-color softcover books, mostly text, the quality is perfectly fine for you and your market, and most readers wouldn’t be able to tell the difference.

Digital printing is also much faster usually, depending on the business model of the digital printing company you are working with. An offset printer may have a queue of 50+ jobs printing 5000-10,000 copies each, and the overall production time is 4-6 weeks. A digital printer can frequently turn jobs in less than 2 weeks as long as the files are properly prepared.

The Important Financial Distinction

As a publisher, here’s the important thing to understand.

Offset printing has much higher set-up costs and charges to get on press and get up and running. From that point, it’s very fast and inexpensive per book. Let’s say getting the press up and rolling costs $1000.

If you are printing 100 books, that’s $10 per book, and cost prohibitive.

if you are printing 1000 books, that’s only $1 per book

If you are printing 10,000 books, its 10 cents per book

This is why your unit costs drop significantly as your print run increases. The gamble in publishing is printing enough in the first print run to cover your immediate and near-future needs (1 year?) to drive down unit costs, without overprinting and winding up with excess inventory in your warehouse or garage. The most expensive unit cost is for the books you never sell.

Digital printing is again similar to a copier or laser printer.

There are minimal set-up charges if any, and the unit cost is relatively static. Per copy reductions are usually for business reasons more than actual cost savings (VS), and that’s why printing 200 copies might save a few cents on the unit cost.

Digital printing has the *gigantic* advantage that you don’t have to forecast sales, try to determine the ideal print run, and commit significant financial resources to paying for a big print run. Downside is the unit cost is usually significantly more than offset printing, and doesn’t improve over time. Less risk and commitment, less reward and profit.

Comments are closed